An Irishman’s Diary

IT’S A BIG generalisation, but natural catastrophes usually seem to strike very poor parts of the world: earthquakes and floods piling desolation upon misery in Pakistan, Haiti, Mozambique and Bangladesh.

One suspects, however, that the God of angry nature is distributing brutal shocks with less respect for the wealthier nations as climate change accelerates, Japan being a recent case in point.

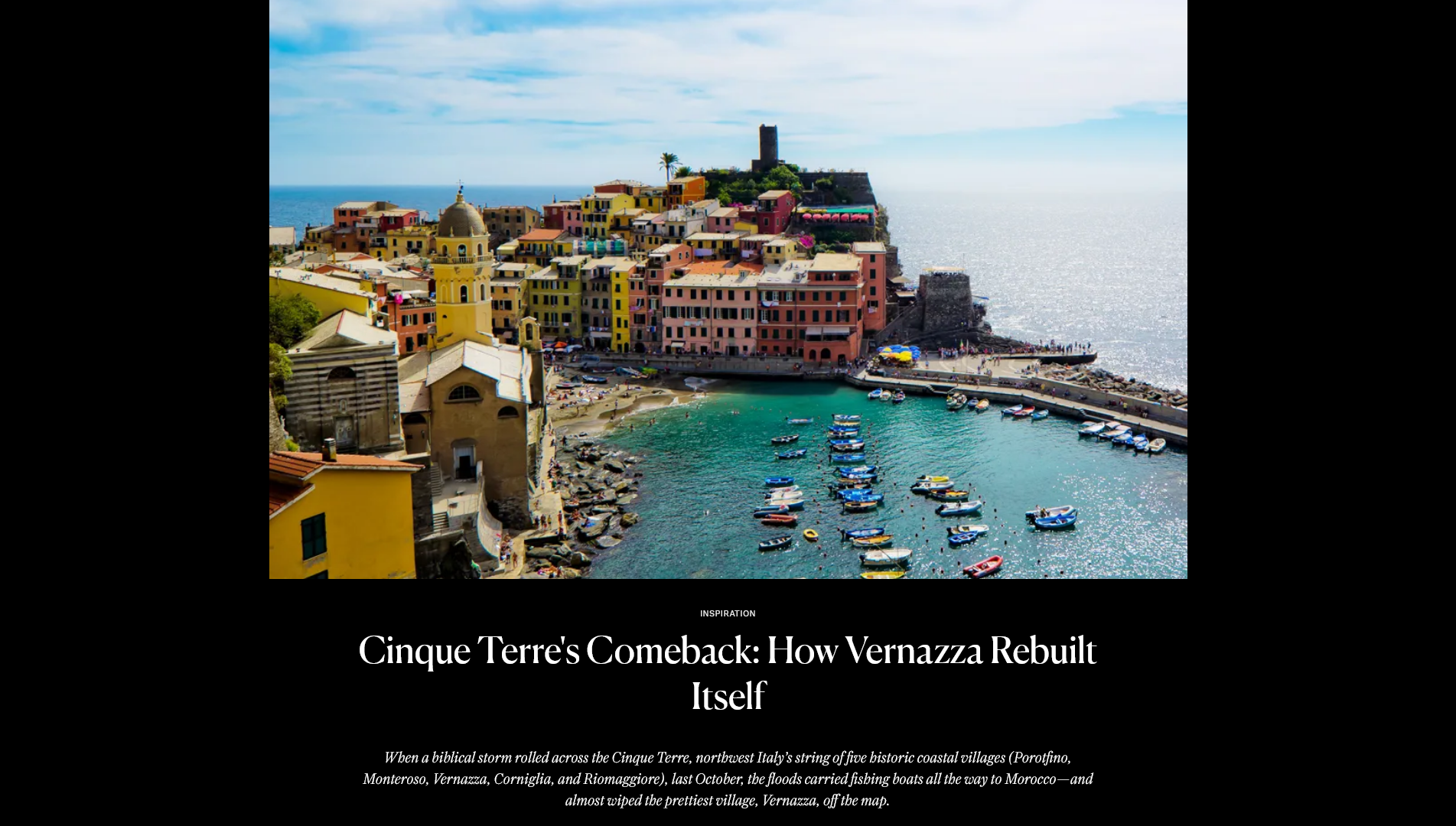

Nevertheless, it came as a grim personal awakening to learn that the village of Vernazza, jewel of Italy’s Cinque Terre, had been half-buried under the detritus of multiple landslides after unprecedented rainfall last October.

We – my wife and three close friends – had been foolish enough to come to think of Vernazza as a safe haven against whatever ills life dealt us.

And unlike most holiday destinations, it also seemed to have remained a special sanctuary for its very rooted inhabitants.

Sure, they grumbled about the thousands of tourists who flooded this very small village (pop. 975) every day during high season, though many of them owed a high standard of living to those same interlopers.

However, because no hotels are permitted in this UNESCO World Heritage site, most tourists leave by early evening. At night, the piazza and single shopping street, the Via Roma, quickly recover the atmosphere of an intimate and hard-working Ligurian village.

Having stumbled upon a delightful apartment, we have returned to it annually for more than a decade. Very slowly indeed, but equally surely, we have made good friends there, who have welcomed us into their lives, and often into their homes.

We have watched as their children grew, and their businesses flourished.

We call in every day to Michelle and Antonio Greco’s hospitable gallery, hungry for more of his delightful and often challenging work.

Last year marked yet another new and happy connection with the village.

Our friend Phelim, an accomplished amateur pianist who wears his 75 years very graciously, was invited to accompany two sopranos and a local tenor at a charity concert. The event was a sell-out.

The next day the mayor approached Phelim in the street to congratulate “il maestro irlandesi”. He insisted that next year the concert venue would have to be Vernazza’s three-sided piazza – the fourth side is the sea at high tide – so that the whole village could enjoy it.

Phelim’s overnight stardom had started a few years earlier. He used to play occasionally on a rather bockety upright piano in the Blue Marlin. One night Julia, a professional American soprano who had married Paolo Basso, the owner/manager of our favourite restaurant, Il Capitano, joined him in song.

Young backpackers found themselves listening to a heart-stopping rendering of O mio babbino caro whether they liked it or not. They seemed to love it.

The Blue Marlin was filled with magic that night, but last October it was filled with mud and rocks. So was every little business on the Via Roma, including Antonio’s gallery, and half the restaurants on the piazza.

Il Capitano luckily had its doors closed on the night of the floods, and was also on the side of the piazza furthest from their terrifying brown surge down the Via Roma and into the sea. Its interior was thus spared.

A small mercy, which did not extend to three elderly citizens whom the surge swept out to sea.

The village’s magical warrens of residential streets are happily mostly on higher ground. But the torrents, toothed with boulders, have cut off gas, water and, ironically, drinking water, completely from the village. The entire population remains evacuated two months later.

The very root of Vernazza’s special qualities was also the source of its shockingly violent and destructive inundation.

For many centuries, the vertiginous hillsides above the Cinque Terre’s five villages were transformed into stone-walled terraces by the hardy inhabitants.

Like Aran Islanders, they carried seaweed up from the coast to fertilise them. They carried earth down from inland valleys.

Their terraces produced a wealth of first-class fruit, vegetables, vines and herbs. Like all Ligurians, they claim to have invented pesto, and maybe they did.

In the 19th century, railways began to offer young people an easy exit from the hitherto isolated region. The rewards of hard labour on the terraces were outbid by the naval yards of nearby La Spezia.

The sophisticated water channels engineered by generations of stone masons grew blocked as the abandoned terraces collapsed over the years. In an area already geologically unstable, the flood-propelled deluge of millions of tons of loose rocks was an accident waiting to happen.

Recent attempts to restore the terraces came too late and achieved much too little.

Emergency services and an army of local volunteers continue to attempt a clean-up today, which heart-breakingly reveals new damage with every advance.

No one knows when Vernazza’s bars and restaurants, foodstores and galleries, will be able to receive visitors again. Nor how permanently scarred its beautiful face will be.

But the villagers are fighting for their home place, and will not give up.

The oldest generation still remembers grinding poverty, hunger and typhoid.

They have a long and honourable history of battling great odds, including a fascist government and Nazi occupation.

Their ancestors built a terrace system longer, yard for yard, than the Great Wall of

China. This generation won’t let a bit of hard labour break their spirit.

For a dramatic daily account of their struggle, see www.savevernazza.com