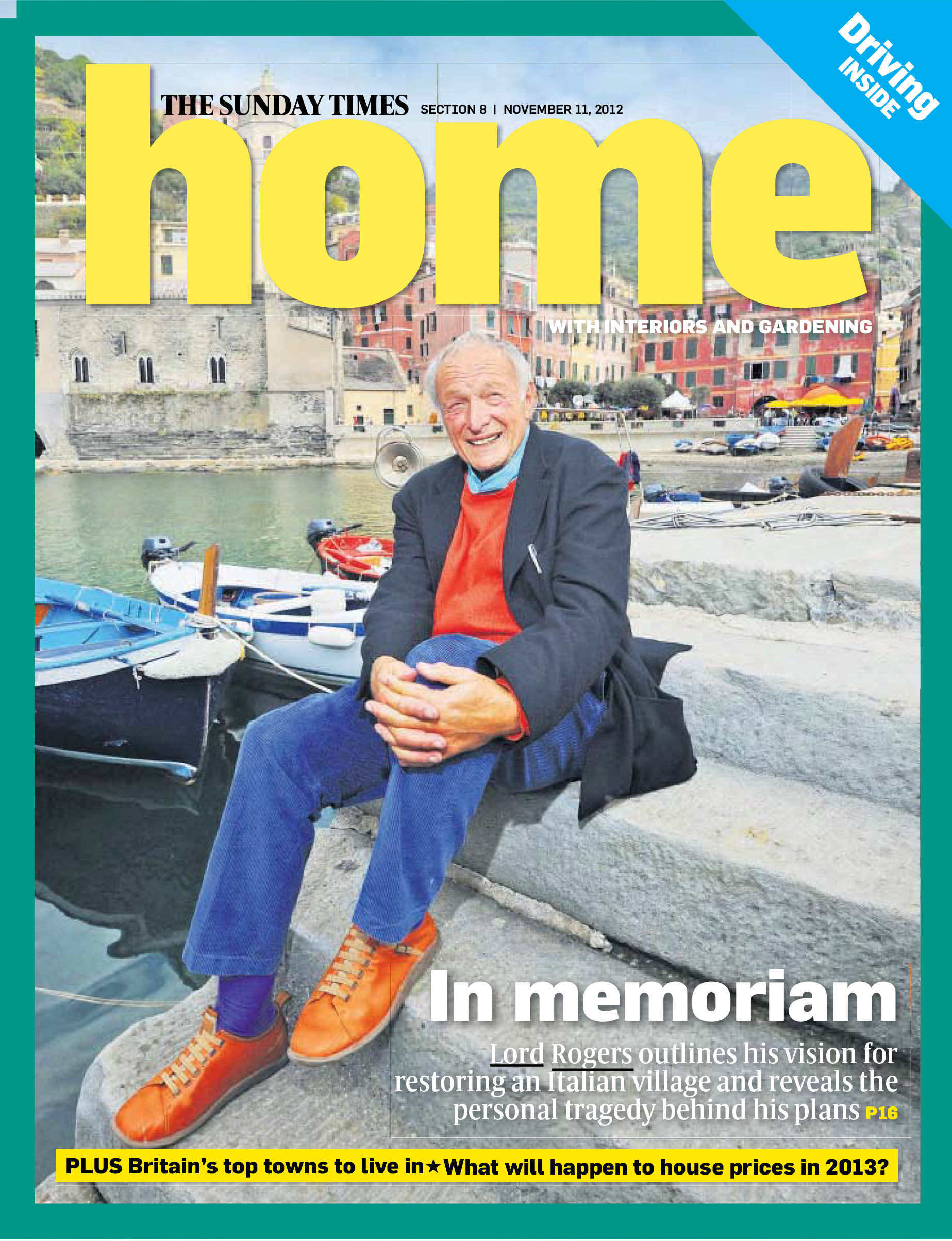

In Liguria’s Coastal Hills, a Storm’s Fury Brings a Struggle for Restoration

VERNAZZA, Italy — When Unesco added the Cinque Terre, five medieval coastal towns perched along the Ligurian Coast, to its World Heritage List in 1997, it cited “the harmonious interaction between people and nature to produce a landscape of exceptional scenic quality.”

Nature broke that pact on Oct. 25 when a violent downpour unleashed unprecedented fury on the town of Vernazza and the surrounding hills here along Italy’s northwestern coast, provoking dozens of landslides that swept a sludgy river of earth, trees, cars and debris onto the small seaside settlement. The bodies of three townspeople swept out to sea by the storm were recovered weeks later in French coastal waters.

Vernazza caught the brunt of the storm, but the picturesque walking paths that link the five villages, an excursion that draws at least one million visitors a year, according to statistics provided by the Cinque Terre Park, were washed out in several spots, and are now off limits.

Locals old enough to remember World War II said the storm had caused even more devastation to the area, said Michele Sherman, a New York native turned Vernazza resident and a supporter of one of several fund-raising efforts, Save Vernazza, recalling that day’s tales of heroism and destruction.

Two months along, much of the mud and debris — which reached about 13 feet, just below the height of first-floor balconies — has been cleared from Vernazza’s main street, which was a lively succession of restaurants, bars and shops doing a brisk tourist business.Continue reading the main story

Related Coverage

AdvertisementContinue reading the main story

Barely a quarter of the town’s 600 residents have returned to their homes, but the alleys resonate with the sounds of heavy machinery, drilling and hammering. Though dressed in the neon colors of civil protection and public safety workers, many of the crew members are local volunteers, men and women from Vernazza or nearby towns, come to give a hand as best they can.

Matteo Barletta, an architect charged with mapping the damage done to the town’s buildings, said that several teams were at work on various aspects of the reconstruction, and that a list of priorities had been set.

“The bakery, pharmacy, tobacconist, bank, fish shop and butcher, these are to reopen to reactivate the town,” he said.

Said Mayor Vincenzo Resasco, speaking in his office high on a hill, where it was spared from the waters: “There’s a lot of work to be done because Vernazza is still not secure. The territory isn’t in the condition to withstand even normal rainfalls.

“The real problem is that if we don’t get money soon, we’re going to have to stop,” he said, adding wryly, “and there isn’t a lot of money in Italy these days.”

Securing the town, the mayor explained, includes painstakingly restoring the stone walls that delineate the terraced hilltops that surmount it. “With the stones that came down, we’ve recovered enough to build a second wall of China,” Mr. Resasco said.

These man-made terraced patches where vines and olive trees have been cultivated for centuries once ensured the survival of the five villages, which were best reached by water until the advent of the railway.

Tourism changed the Cinque Terre, and not necessarily for the better, said Claudio Frigerio, a retired union worker and local activist who has long lobbied for a more environmentally conscious approach to the area’s development. While tourism has been a lifeline, the crowds sometimes give the walking paths a rush-hour intensity. Tour groups and cruises can swell visitors here to around two and a half million a year, too many for critics.

And as tourism supplanted farming and fishing as the town’s chief economy, regular maintenance of the terraced hills lagged, an oversight that many now say was a contributing factor to the devastation of Oct 25. In 1951, about 3,500 acres were cultivated in the Cinque Terre. Today, there are fewer than 275, according to Vernazza town officials. “As we saw, the territory wasn’t able to stand the impact of the rain; the land was already in a state of degradation,” Mr. Frigerio said.

As a part-time farmer of one of those terraced lots, Mr. Frigerio is the first to admit that growing crops on the unevenly terraced slopes overhanging the Cinque Terre is “physically demanding and not in the least profitable,” but “it is a necessity,” he said. To lose the landscape, as well as the various paths linking the towns, “is to lose the area’s identity,” he said, something that will hurt its value as a tourist destination.

However, persuading young people to take up the rigorous work of farming the steep slopes may be, well, an uphill battle. “It’s easier to rent three rooms a year instead of farming up a hill and earning very little,” said Daniele Moggia, a 36-year-old volunteer at Vernazza City Hall. But the calamity “made us understand the importance of preserving the environment and farming.”

The Cinque Terre is one of the few rural areas in Italy where people don’t leave “because there is work here,” he said.

Angelo Maria Betta, mayor of Monterosso al Mare, the other Cinque Terre town badly damaged by the storm, cannot wait to reopen flooded businesses for the spring season. “If we don’t fix the Cinque Terre, we’re going to make a hole in the local economy that’s going to be hard to fill,” he said. Officials say the paths linking the towns will be open by Easter, and they vow to restore the towns as quickly as they can.

“Vernazza will be rebuilt as before,” Mayor Resasco promised. “I have made a pact with citizens to make the town better than it was. It is a message of hope, not resignation. We are from Liguria, and we are stubborn.”